Murtaza Vali on Events in a Cloud Chamber

INSTALLATION / MIXED MEDIA

26.11.17 to 26.12.17

In 1969, the pioneering modernist painter Akbar Padamsee made a short film called Events In A Cloud Chamber. It was his second, after Syzygy, an eleven-minute silent black-and-white stop-motion animation in which shifting permutations and combinations of lines, shapes, letters, numbers, and diagrams, inspired by Paul Klee’s Pedagogical Sketchbook, danced across the filmic frame. Shot on a 16mm Bolex, Events In A Cloud Chamber, ran for six minutes and featured a single colour image of a trembling dreamlike terrain. In it, Padamsee tried to ‘reproduce’ one of his own oil paintings using projected light instead of applied pigment, working with tinted filters and stencils to recreate the differently coloured sections of the painting. Shooting each colour individually, he then superimposed the footage to create a composite image that recreated the original painted landscape. This superimposition was done entirely in camera by repeatedly rewinding and placing each layer of colour on the same stretch of film stock. The enigmatic title—which alludes to an early scientific instrument in particle physics used to detect ionizing radiation and which recorded the traces of otherwise invisible, indeed unknown, phenomena—referenced this process of working ‘blind’ in the darkroom, embracing randomness and chance. Produced through a colour reversal process, only one print of the film existed.

Both of Padamsee’s films were made in the context of the Vision Exchange Workshop (VIEW), a revolutionary space for interdisciplinary experimentation and collaboration that he established in April 1969, using funds he received through a Jawaharlal Nehru Fellowship. Padamsee was already quite successful and well-known as a painter by then and was interested in exploring the artistic potential of twentieth-century media like photography and film. The scant surviving correspondence from the time reveals him actively enlisting the assistance of his peers: photographer Bhupendra Karia was tasked with constructing the workshop’s darkroom, while fellow painter Krishen Khanna committed both time and money to a collaborative film project. When initial plans to establish the workshop in Delhi fell through, Padamsee moved the project to Bombay, operating it out of his apartment on Nepean Sea Road through the end of 1972. In addition to providing books, slides and 16mm cameras for use, the workshop also housed a dark room for experimental photography, an etching press for printmaking, and facilities for editing and projecting film—a particularly rare resource for artists at the time. Participants included painters, sculptors, printmakers, photographers, and filmmakers, but also included a cinematographer, an animator, and a psychoanalyst. The spirit of collaboration and exchange extended beyond a ‘mere’ exchange of equipment and ideas; participants now had a structure through which they could experiment with new media by drawing on the specialized skills and technological expertise of others. As Nancy Adajania has suggested, VIEW is the key to recovering the prehistory of new media art in India. It is the stuff of avant-garde legend, the very type of mythic space, brimming with unbridled artistic experimentation, that leaves art historians giddy.

Syzygy was ahead of its time; it received less than enthusiastic responses at the handful of times it was screened. Introducing the film at a UNESCO screening in Paris, Jean Bhownagary, Chief Producer of the Films Division of India, wryly warned the audience: “Please take an aspirin; this film will surely give you a headache.” It is unclear when, where, and how many times Events In A Cloud Chamber was screened. It is also unclear how it was received. An invitation to the opening of an exhibition of Padamsee’s Metascapes at Pundole Art Gallery on 1st February 1974 reveals that it was shown as part of that evening’s programme. However, some time later, the sole print of the film was shipped to an art expo in New Delhi, where it was misplaced. Padamsee, disheartened by the tepid reception to these ventures, did not try too hard to track it down. Events In A Cloud Chamber, which may have catalyzed the subsequent production of experimental artist films in India, a purely formal and abstract practice that rejected the pictorial and narrative impulses of both popular and alternative Indian cinema, was lost.

Ashim Ahluwalia’s Events in a Cloud Chamber, a collaboration with the aging painter who is now eighty-eight, is a quest to retrieve Padamsee’s film, which exists now only as an indistinct and quickly fading memory. Like the lost film, Ahluwalia’s remake is shot entirely on celluloid, 16mm, and Super 8, film stocks with a ‘retro feel’ that has only intensified in the digital era. It begins with an extended sequence of what appears to be heavily degraded found footage, accompanied by a dull jet engine-like rumble. The scratched and weathered surfaces that flicker by disrupt clarity—the intelligibility of the events they capture. Out of the visual imbroglio figures cohere occasionally: a woman, some children, a little boy dressed like Nehru. The real appears or becomes spectral, fugitive. The image clears up, revealing a children’s fancy dress party or competition in a park or backyard somewhere, just as Padamsee’s quivering voice begins to reminisce about his childhood, recounting the beginnings of his lifelong passion for art. Touristic shots of lush green valleys, snow-capped peaks, bustling city squares, and Venetian canals flash by as Padamsee narrates his encounter with Andre Breton during his time in Paris, punctuated with the occasional black-and-white photo of the young painter. The visuals through this entire opening sequence (preceding and accompanying Padamsee’s recollections) are extracted from vintage home movies shot by Ahluwalia’s own grandfather, discovered buried in the back of a cupboard long after his death. Though unacquainted with Padamsee, Ahluwalia’s grandfather was a fellow inhabitant of the cosmopolitan Bombay of the 1950s and 1960s and a rare amateur filmmaker during a decade of unprecedented international mobility for Indians, and Ahluwalia cleverly uses this accident of autobiography to fill an archival lacuna. This gesture, generous and intimate, only strengthens his collaboration with Padamsee, reestablishing a much sought-after genealogical link whose promise had seemed all but lost with the disappearance of the original Events In A Cloud Chamber.

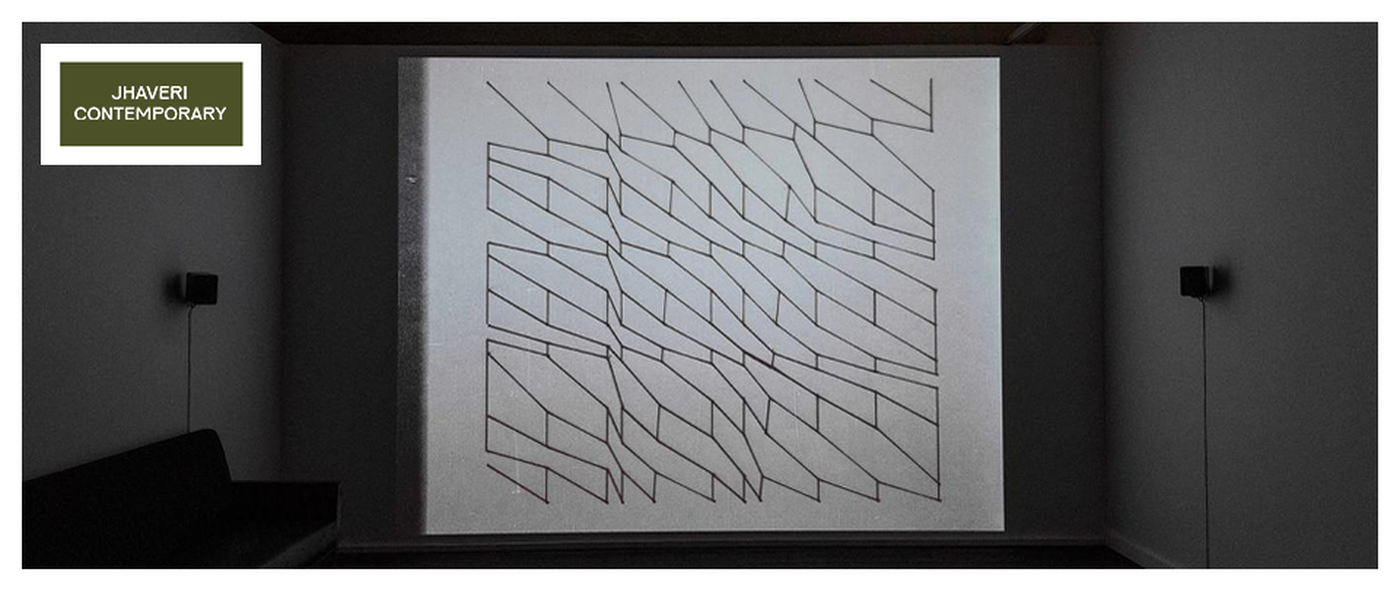

Ahluwalia retains the period feel by using different types of vintage footage through much of his film. Padamsee’s retelling of the ideas behind and the making of Syzygy plays on top of an excerpt of the film itself. Ahluwalia also uses footage excerpted from various Films Division documentaries made at the time. One segment shows Padamsee in his prime, at work, mixing paint, making tea, while discussing his thoughts on art. Another, as Padamsee recounts the lukewarm response to his films, consists of a montage of Bhownagary and a cheeky series of shots of bored film audiences. A sequence of images of musicians and performers accompanies Padamsee’s insouciant response (“There was a lady...a Sarabhai lady”) when he is questioned about the soundtrack. Ahluwalia’s research also uncovers a mysterious empty spool of demagnetized tape labeled “Akbar Padamsee Film” in the Sarabhai archives, occasioning a speculative aside about the musician and singer Geeta Sarabhai and her relationship with, and possible influence on, John Cage, and this provides another illustration of just how connected Indian artists and musicians of the time were with international avant-garde networks. Ahulwalia attempts to recapture some of the cosmopolitan avant-garde spirit of the late 1960s moment by screening his film in a constructed environment that approximates Padamsee’s apartment and the possibility- fueled atmosphere of the Vision Exchange Workshop. The gallery is reconfigured into a simple live/work space where, with archival material to aid in time travel, we are invited back to sit, read, watch, hang out, talk, debate, create, experiment, and imagine. Taken together, Ahluwalia’s installation and film seek to reverse the almost inevitable flattening of the past inflicted by the passage of time and the distortive lenses of history and memory; they attempt a recovery, if only for a short while, of the seemingly limitless possibilities for exchange, experimentation, and collaboration as they once existed in a specific time and place.

Much of the Films Division footage Ahluwalia uses still has a visual crispness to it. Ahluwalia’s Events in a Cloud Chamber, however, begins to pulse and quiver again whenever we see the aged Padamsee, halting and stuttering like his weary voice. Captured on dark, grainy Super 8, Padamsee’s presence is never absent, though he sometimes seems to inhabit the shadows—standing in a corner while he catches and throws a PT ball; nodding off in his wheelchair; slowly sipping from a white mug; animatedly sketching and painting nevertheless. We witness a search and a struggle—remembering events and ideas nearly a half-century old and retrieving specificity from the vagaries of memory. What begins as an attempt to recreate Padamsee’s lost film, to literally re-member it back into existence, expands into a rumination on the vicissitudes of time and (art) history. It reveals and, just maybe, revels in how arbitrary and accidental the processes of both memory and history can be, how being forgotten is the rule, being remembered the exception. It also serves as a heartfelt but melancholic portrait of the artist as an old man. It is, as Ahluwalia says in the film synopsis, “ultimately a ghost story,” asking us whether art can actually ever preclude the inevitability of death and stall our disappearance into the past, into the oblivion of time. However, as a work of art itself, Ahluwalia’s film seems to suggest that the compulsion to imagine and create is transcendent. Collecting, recording, and representing the fast disappearing traces of a past event—a phenomenon as evanescent and invisible as the trail left by a charged subatomic particle—it functions like a cloud chamber itself. And in its last moments, Padamsee’s film is resurrected, now transcendent, glowing, in the way an abstract landscape painted out of light gradually, and sometimes magically, comes together.

Murtaza Vali

Murtaza Vali is a Brooklyn-based writer, art historian, and curator. An independent critic since 2005, his reviews, essays, profiles, and interviews have appeared regularly in Artforum.com, ArtReview, Art India, Bidoun Magazine, and ArtAsiaPacific, where he is contributing editor and was co-editor of their 2007 and 2008 Almanac, a year-end review of contemporary art across Asia. He has written essays for nonprofits and galleries around the world, most notably for monographs on Emily Jacir, Reena Saini Kallat, and Laleh Khorramian. He has been a visiting critic at Yale’s School of Art and Cornell’s College of Architecture, Art and Planning. As winner of the Winter 2010 Lori Ledis Curatorial Fellowship, Vali curated Accented at Brooklyn’s BRIC Rotunda Gallery (2010) and recently edited Manual for Treason, a multilingual publication commissioned by Sharjah Biennial X (2011). He holds an MA in art history and archaeology from New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts.

.jpg)