The Gangster of Dagdi Chawl

The Indian Express 03.09.2017 by Dipti Nagpaul

A pistol is no biggie. To kill with a knife takes real daring.” Sudhir Sawant (name changed) allows his words to sink in before he goes on. “With a knife, you have to walk up to the target, deal with his security, stab him till he is dead, and then walk away from the crime scene. You cannot run because that can alert others. A gun can be used from afar, so anyone can kill with a pistol,” says Sawant.

Except for the occasional bragging, Sawant has little in common with the swashbuckling underworld shooter so beloved of Bollywood. His residence near Mumbai’s Lalbaug is a tiny chawl room, where he lives with his wife and two children. At 58, he is retired and diabetic, and “not a spot on the hulk” he used to be. He wants to know if Ashim Ahluwalia’s Daddy, a film on gangster-turned-politician Arun Gawli, his former boss, will glamourize the underworld again or, for once, fairly depict their “tough and unpleasant” lives.

Sawant was a shooter, bodyguard, and a trusted lieutenant of Gawli before he gave it all up in order to have a family. He joined the gang in 1987, a crucial year. Until then, the gang was known as BRA, after the initials of its three leaders, Babu Reshim, Rama Naik, and Arun Gawli. That year, within a span of months, Reshim was killed by a rival gang, and Naik died in an encounter, leaving Gawli as its sole leader. “Till then, Gawli has been in the backdrop while Rama Naik and Babu Reshim led the BRA’s activities,” says Deepak Rao, a city historian.

Initially, the BRA provided muscle power to other gangs, like that of Dawood Ibrahim’s, until they took control of Girangaon (the erstwhile mill area) through extortion and “protection.” Reshim and Naik were the known criminals, and Gawli rarely found a mention in news reports. According to another former gang member, who did not wish to be named, Gawli was often the shortest man in the room and, hence, hesitant to take the lead. “But his need to prove himself made him the one who got things done.”

Sawant joined Gawli at a time when the gang was falling apart. Everyone was under suspicion after Naik and Reshim’s deaths. “It also meant that Gawli was the next target. So he started recruiting new members, and I was one of them,” says Sawant.

He, too, was on the run. Once an office boy with the LIC, Sawant had been drawn into a fight with a bunch of brawling outsiders in his neighborhood. “I ended up killing one of them, and that made me their target,” he says. Gawli stepped in to protect him and invited him to join the gang.

By then, Gawli had already turned into a Robin Hood of sorts. People from Dagdi chawl and the neighboring areas would come to him with their problems.

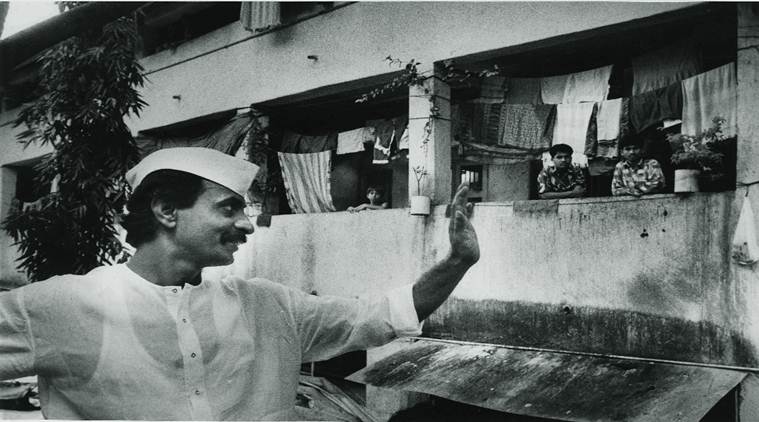

“The 1982 mill strike had shut down mills, and a large number of young men were unemployed. Many of them strayed into crime. What set Gawli apart was that he started something like a salary system. He would also provide financial aid to the family if a member was arrested or killed. They started to look upon him as a savior,” recounts a former resident of the chawl. He would also sort out more mundane problems, from water shortages to school admission and small and big skirmishes. At the courtyard within the chawl, Gawli held a daily durbar to hear such pleas, winning him the unconditional support of the residents of Dagdi and beyond. As he rose to power, the chawl became his first and fiercest defense.

At Dagdi Chawl, in the Agripada area, it takes all of five minutes for an outsider to be sized up and questioned, even though “Daddy,” aka Gawli, isn’t home. This is the gangster-turned-politician’s turf, and the writ of law totters at its entrance. On the ground floor, the residence of the Gawlis shares space with the offices of Akhil Bhartiya Sena (ABS), the political party launched by Gawli in 1997.

In the early 1900s, the chawl used to be like any other, with wide stairways, high ceilings, and thatched roofs, says Vrushali Telang, who carried out research for the film Daddy. “But later, basement rooms were constructed for hiding, and the alleyways were made narrower for a quick getaway into the maze-like Agripada,” says Sawant. After 1987, as gang wars erupted across the city and the Mumbai police-sanctioned encounters, Gawli and his gang stayed put in the chawl, away from the long arm of the law.

It helped that he had the support of every chawl resident, who allowed him to build holes and cavities under beds, in kitchen floors, and behind cupboards as hideouts in case of a police raid. The lesser-known members of the gang were passed off as chawl residents. “But over time, the cops smartened up. They would show up with a list of residents in each room and do a head count,” recounts Sawant. “One day, I spent two hours cleaning the common bathrooms as I pretended to be a sanitation worker. Another time I was the local butcher and chopped hens for three hours,” he says.

When Gawli was behind bars, his gang could operate without a hitch from Dagdi. “His wife, Asha Gawli, became his strongest ally and greatest confidante, taking over the reigns in his absence,” says Ahluwalia.

Formerly Zubaida Mujawar, she is close to 15 years his junior. Gawli married her when she was 16, much against his mother’s wishes. “He was hardly around when we were growing up. But my mother handled everything, with help from her relatives. They moved in with us and made sure we had a very normal childhood,” says Geeta, 34, the eldest of his five children. She and her siblings, however, were not allowed to play in the open.

By the early 1990s, Gawli had also branched off into real estate, brokering land deals for a price. In 1994, he had close to 300 men working for him, says Sawant—about 50 were a part of his trusted team. The rest were mostly contract killers.

But it wasn’t all guns and roses. Sawant recalls the early years when they had little money and fewer guns. “We shared one pistol between 20 shooters; each had to take turns to carry out the assignment. Sometimes, we just used the gun to scare our target while using swords and knives to carry out the actual murder,” he says.

Gawli’s clout got bigger when, in the late 1980s, Shiv Sena chief Bal Thackeray called his team “amchi muley” (our boys), pitting him against Dawood Ibrahim. However, the two had fallen out by the mid-nineties and Gawli launched his own party, ABS, in 1997, while he was still behind bars. “Almost the entire Gawli gang had been encountered by the police. Politics was the only way to survive,” says Sawant. Others say that the party, which was quite popular at the time, was Gawli’s way of standing up to Thackeray’s Sena.

That confrontation did not end well for Gawli. He was arrested in 2008 in an extortion case and let out on bail three years later. A few months later, in 2012, he was convicted for the murder of a Shiv Sena worker.

And yet, in the Lok Sabha elections of 2004, Gawli won over 90,000 votes in South Central Bombay and became an MLA. “This was a major embarrassment for the police force,” says Rao. “They now had to protect the man they had chased for years.”

Most of the police force remembers him not as a classic fearless gangster but as a clever fox who managed to survive, often placing safety before bravado. One of the most popular anecdotes about Gawli, now 64, involves his arch nemesis in khakhi, the slain encounter specialist Vijay Salaskar, who gunned down at least 11 shooters of the Gawli gang. On the day of voting for the 2004 Lok Sabha elections, Gawli refused to step out to vote because Salaskar was in charge of securing the Dagdi chawl area. “What is Salaskar doing in my area on election day? Woh yedaa officer mera murder kar dega (That mad officer will murder me),” he had said to much-amused journalists.

When Sawant was released from jail in 1995, he decided to give up on crime. His childhood sweetheart had waited for him all those years. “For the first few years, the cops would pick me up whenever they wanted. But life is good now. I survived the toughest phase when we lost over 90 of our boys to encounters,” says Sawant, who believes he wouldn’t have lived had he harmed an innocent life. “It was our rule: Kill the rich, the mafia, the politicians, and the cops, but never harm the poor and innocent.”

Despite the wealth they acquired, Sawant, Gawli, and the handful of retired gangsters who survived the encounters and gang wars chose to stay where they had tasted power. “It’s because unlike Dawood, Chhota Rajan, and others, we had nowhere to go. We were local boys, rooted in our city and its people. That’s why Daddy is known as ‘the only one who did not run away’.”

(With inputs from Mohamed Thaver)

.jpg)